Science at Storytime: Recent Curriculum Changes - Science of Reading Programs

After decades of debate, the reading education industry is finally encouraging more explicit and systematic phonics instruction: a change instigated by the release of a 2018 APM report and documentary series by Emily Hanford, which illuminate the long-term literacy struggles among students receiving balanced literacy instruction. While these moves are encouraging, the actual implementation of psychology-based, data-driven curricula may be daunting for new and seasoned educators alike. Today, we unpack the myriad challenges - and benefits - of revising reading curricula to reflect the findings of reading science.

According to a comprehensive review of today’s most popular literacy materials by Education Week, educators are increasingly focused on decoding: how early readers convert words on a page into spoken language. Based on evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience, skilled readers focus on letters in the words to identify what words say, as opposed to pulling from pictures or sentence flow to predict a word. While advocates of the structured literacy classroom, which emphasizes the scientific importance of decoding, acknowledge that good readers attend to story structure and syntax, these readers also need to be able to decode words without pictorial or syntax cues.

Contrary to what the sudden tide of science-based curriculum “rewrites” may suggest, the research driving these changes is not new. If anything, the number of students falling behind in reading in the wake of the pandemic is revealing the inadequacy of literacy education in a striking number of elementary classrooms. Although its principles often contradict or simply disregard the science, balanced literacy remains deeply embedded in early reading instruction. Many programs and teacher guides encourage students to utilize a strategy known as three-cueing or MSV: Meaning, Structure, and Visual. Using this strategy, students often over-rely on a story’s visuals and/or sentence structure, leaving them guessing at words in the present; and in the long-term, unable to read deeply and with genuine enjoyment.

Recent curriculum changes are heralded by some of the most prominent names in the field, including Lucy Calkins, creator of the Units of Study for Teaching program used by about 16 percent of elementary and special education teachers. These lessons will incorporate more explicit phonics instructions and remove questions that prompt students to use pictures or context clues for word identification. Similar changes have been made in The Reading Strategies Book, a popular resource written by Jennifer Serravello. In the updated edition, Serravello cites sources from developmental psychology and cognitive science, supporting the dominant thesis that phonics instruction produces skilled readers through orthographic mapping. By "gluing” spelling and sound together in memory, Serravello writes, children reach a point of fluency at which words can be retrieved automatically.

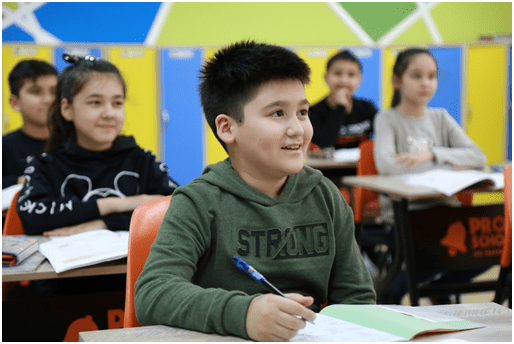

Collectively, these revisions suggest a newfound embrace of reading science. Yet some industry leaders are concerned that curriculum overhauls will yield only surface-level change. Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive scientist and psycholinguist, worries that revisions may be enough to satisfy new laws concerning reading science and phonics instruction, but that it will be difficult to properly support the teachers and schools tasked with implementing these changes. To truly do better for our students, reading research must be both accessible and actionable for teachers and schools at large. Jan Burkins and Kari Yates, authors of Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom (2021), emphasize the importance of accessibility and human energy in the re-balanced literacy classroom. Above all, while teachers should have access to reading science, we must also recognize the limited time, energy, and school-based resources among educators and parents and distribute our efforts accordingly.

The work ahead of us is collaborative, spanning from the level of individuals, to schools, to large-scale organizations such as Calkins’ think tank, Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. Because understanding the research is different from applying it, translational work between cognitive psychologists and educators will underpin a practical application of reading science. The urgency of this work is heightened in the wake of COVID-19 when many schools are facing major reading gaps, in addition to the challenging personal circumstances present in any classroom. Teachers are asked to attend to these needs in addition to accessing and effectively applying the latest research on reading science. Consequently, simply stamping a “science of reading” seal on a resource and putting it in teachers’ hands doesn’t necessarily offer the knowledge, understanding, or time they need to change their instruction, says early literacy expert Wiley Blevins. By offering cross-disciplinary training for reading teachers, the conversation about reading practices can lead to a place of transparency among teachers, scientists, and curriculum writers - and, most importantly, a place of achievement and enrichment for young readers.

Take-Aways:

- Within the last year, the reading education industry has shifted toward more science-based literacy instruction with an emphasis on phonics and decoding.

- Notable authors and educators in reading science have revised their curricula to reflect this change in perspective, including Lucy Calkins of the popular Units of Study curriculum and Jennifer Serravello, author of The Reading Strategies Book.

- Phonemic awareness and science-backed strategies are essential to students’ long-term reading success, but implementation of these curricula changes may be challenging due to constraints on time, energy, and other resources.

- With collaborative work between educators, schools, psychologists, and other researchers in the field, we will continue to progress toward more science-driven, structured, and phonics-based literacy programs.

Start Teaching Reading for Free Now!

Access Level 1’s four interactive stories and the accompanying supplemental resources to teach elementary students how to read. No credit card is needed. Join the 42,635 teachers and students using our reading program.