The Midlothian Model: Science-Based Reading Interventions using Phonics-Centered Literacy

As classrooms continue to learn and grow in the era of COVID-19, researchers and educators are noticing major changes in literacy levels – and students’ reading scores are reflecting their observations. In the spring of 2021, a national analysis of the test scores of 5.5 million students found that students in each grade scored three to six percentile points lower on a widely used test, the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP), than they did in 2019. Even before the pandemic, nearly two-thirds of U.S. students were unable to read at grade level, and numerous studies have documented poor reading progress among U.S. students during the pandemic. Fortunately, certain school districts are implementing science-based reading interventions to reverse these trends. In today’s newsletter, we continue our discussion of reading science, focusing on remarkable efforts at Vitovsky Elementary and other Midlothian public schools where research-backed interventions bridge key gaps among struggling readers.

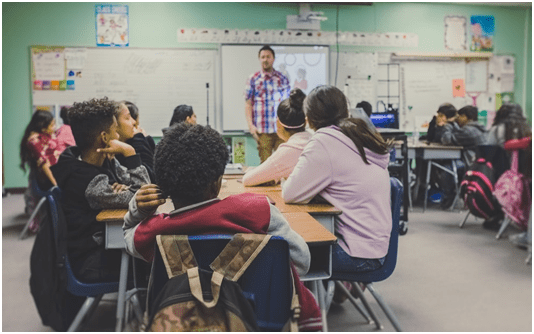

While producers of major reading curricula have recently announced changes in their lesson plans to reflect current science, school leaders in the Midlothian school district have championed small-group learning and science-driven phonics instruction for the last five years. At Vitovsky Elementary, where nearly 60 percent of students come from low-income backgrounds and a quarter are learning English, the decision to implement science-based reading interventions five years ago was one of necessity, not educational experimentation. Texas students’ reading scores have long lagged behind other states’ scores: in the last decade, the state’s reading performance in fourth and eighth grades hovered in or near the bottom 10 states, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress or “The Nation’s Report Card.” Inevitably, teachers fear that reading performance will only be worsened by the pandemic, prompting a recent Texas law that pulls from the already-active Midlothian model. The legislation requires that all public schools offer intervention for students lagging behind in literacy, detailing 30 hours of focused tutoring or matching with highly rated educators for students who failed Texas tests.

At Vitovsky, reading teachers express gratitude that early reading interventions are already embedded into their school culture. On their campus, where more than 120 children in fourth and fifth grade alone require the elevated level of tutoring after failing at least one state reading exam, building in early-morning reading instruction is no easy feat. And while masks are essential, they also complicate phonics instruction. Behind a mask, youngsters and teachers cannot see each other’s mouths, teeth, and tongues as they form sounds, presenting unexpected challenges for instructors and students – especially those learning English as a second language. Logistically, the fulfilment of the recent Texas legislation is complicated without adequate funding, scheduling, and ample tutors to support teachers, especially in small and rural school systems. While educational leaders hoped that their feedback about these barriers would catalyze changes to the bill, Rep. Harold Dutton, D-Houston, chair of the public education committee, said the Texas governor did not express interest in changing the law and did not indicate any plans to call another special session to address the issue.

Despite these setbacks, schools are still working to prioritize literacy and help kids recover with the support of volunteers and nonprofits that promote science-based literacy. Many teachers are also eager to attend “reading academies” focused on science-backed strategies, re-training them to teach students about the core sounds that make up words based on research about the way our brains decode written language. Educators remain optimistic that students – not just in Midlothian, but in any state – can bounce back from the literacy lags of COVID-19. Since implementing research-based and phonics-centered literacy interventions five years ago, Midlothian’s reading scores have consistently beat the state and regional averages. Vitovsky, the district’s elementary school with the highest poverty rates, has stayed relatively in line with the state on standardized tests in recent years. Across departments, subject matter, and state lines, teachers – and, hopefully, legislators – are called to recognize the necessity of literacy. Ultimately, literacy must be regarded as a life skill: not only does it allow students to read and enjoy literature, but it also empowers them to access and navigate “the language of social studies, science and knowledge,” said Sharon Vaughn, director of the Meadows Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Take-Aways:

- On average, U.S. students’ reading performance has been negatively impacted by the pandemic, as reflected in recent state and national test scores.

- Noting these trends, the Midlothian Public School District in Texas provides a glimpse into what science-backed reading interventions can look like for schools with state funding, scheduling support, and training for teachers.

- Phonics-centered, research-driven interventions at Midlothian have correlated with increases in their students’ state scores, offering hope that young readers can bounce back after the pandemic with science-backed instruction.