What Does It Take To Be a Good Reader

At Reading Teacher, we are motivated by a fundamental question: what does it take to be a good reader? The seemingly simple quandary has fostered a considerable amount of controversy; and after a worldwide shake-up in elementary education, it’s increasingly difficult to determine what today’s young readers truly need to become good readers. While reading researchers and teachers continue to debate, it’s clear that a combination of systematic phonics, word recognition, and fostering a love for reading will help youngsters become more confident, competent readers.

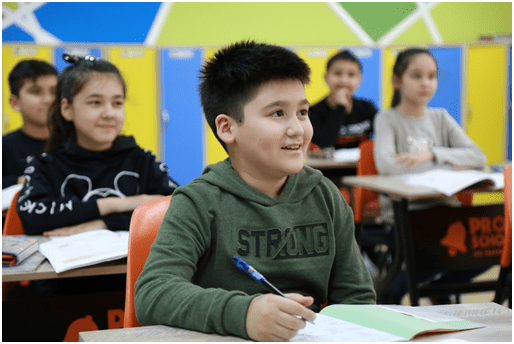

Inevitably, our understanding of what it takes to be a good reader in 2022 is partially hampered by COVID. Nevertheless, we know that systematic phonics exposure is one of the keys to early literacy. At Churchill Primary School, a small school in the Latrobe Valley of Australia, educators share the success of their “purist” phonics-based approach. When Churchill Primary switched from balanced literacy to phonics-based reading instruction in 2018, 31% of its Grade 3 students scored in the bottom two bands in Australia’s National Assessment Program for Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). In 2021, after three years of systematic synthetic phonics (which focuses on reading out and blending in reading), there were no students in the bottom two reading bands; a remarkable 75% scored in the top three bands, exceeding the state average of 60%. Churchill’s teachers focus heavily on teaching students the 44 sounds, or phonemes, in the English language and the letter combinations that create them: the basis of synthetic phonics. Anecdotal support for phonics - and its role in nurturing lifelong, successful readers - will likely be strengthened by a long-awaited £1m UK-based study of the effectiveness of popular phonics programs. Funded by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), the trial will assess the results of two systematic, synthetic phonics-based literacy programs used in 25% of UK schools.

Both anecdotal and research-driven support for phonics are instrumental in the development of reading curricula that ultimately foster competent readers. Yet phonics instruction is just one part of becoming a good reader: quality phonics instruction enables word recognition, another pillar of reading competency. In the so-called “4 stages of learning to read", children can recognize almost all letters by the end of kindergarten and navigate various syllables by the end of first grade; they can then recognize common letter patterns by the end of second grade, and become masters of decoding words using phonics by the end of third grade.

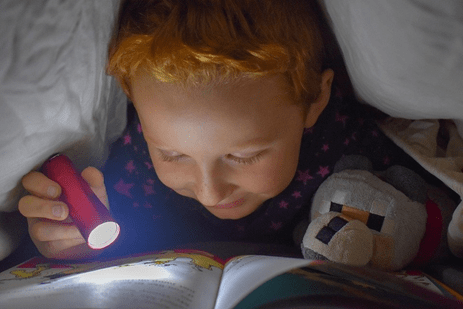

Or, at least, that’s the goal: any parent or educator knows that for most children, becoming a good reader cannot be reduced to 4 simple steps. Fundamentally, good readers also enjoy reading - and data rooted in the science of reading support this. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) found that children from disadvantaged backgrounds who habitually read for pleasure still outperform their peers in international assessments. Driven by excitement, good readers are also more likely to pursue a wide range of texts. Educators and parents can help light this internal fire by joining children on their reading journeys, reading together, and using decodable readers and culturally relevant chapter books with thoughtful storylines. Coupled with early instruction in systematic phonics and word recognition, these foundational steps will help youngsters develop into good readers, multi-dynamic students, and thoughtful adults.

Take-Aways:

- The question of what it takes to be a good reader is complicated, yet essential for educators and researchers to consider as new reading curricula emerge based on the science of reading.

- A strong foundation in phonics and word recognition, coupled with a simple love for reading, emerge as three critical factors in the profile of a good reader.

- Given the impacts of COVID and the individuality of each student, educators and parents are encouraged to pursue a wide range of texts, honor the unique interests and experiences of their students, and embark on lifelong reading journeys alongside them.

Start Teaching Reading for Free Now!

Access Level 1’s four interactive stories and the accompanying supplemental resources to teach elementary students how to read. No credit card is needed. Join the 42,635 teachers and students using our reading program.