Picking up the Book After Virtual Literacy Instruction: The Current Challenges of Literacy Instruction in the Multi-Reading Level Classroom

After an extended period of virtual literacy instruction, it can be challenging to find appropriate resources and tailored reading plans that transition smoothly from one lesson to the next, especially in a classroom reading at a variety of levels. In today’s newsletter, we present a classroom case study and illuminate the current challenges of literacy instruction in a multi-reading level classroom, before reviewing strategies that can help schools advance young students reading at different levels.

Heather Miller, a first grade teacher at Doss Elementary in Austin, TX, is one of many teachers who radically shifted their reading instruction upon returning to the in-person classroom. This fall, Miller had to backtrack from writing full sentences with her first graders to writing single letters. While Miller’s students are struggling to read at their grade level, they are also falling short of social and developmental milestones: she sometimes stops class to mediate disagreements, or to assist students whose fine motor skills were delayed by prolonged virtual instruction. “My kids are so spread out in their needs,” she told the Hechinger Report; after virtual instruction, “there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.” Miller’s classroom is one of many that are experiencing the long-term impact of virtual instruction during the pandemic. A recent report by Amplify Education Inc., which creates reading curriculum, assessments, and interventions, found that children in first and second grade experienced dramatic drops in reading level scores compared with those in previous years. Learning loss is exacerbated among low-income, Black, and Latinx students compared to their white peers, according to data analyzed by McKinsey & Company.

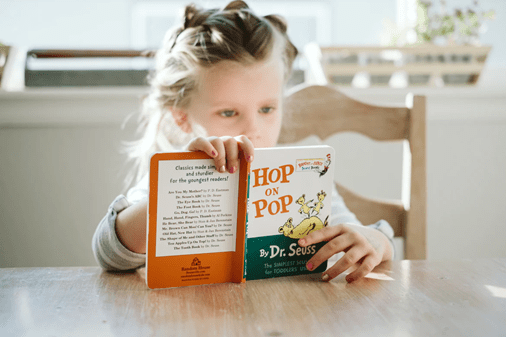

In consideration of these barriers, students can still have a positive literacy education with thoughtfully applied strategies from teachers, parents, school psychologists, and other supportive adults. In her first grade classroom, Miller divides her students into several small groups, tailoring activities typically used by younger grades to help students reading at the lowest level. For two hours a day, she works intensively with this group; for other students, she supplies various reading “tools”, such as hollow phones that encourage students to listen to themselves read and reinforce connections between sounds and written words. Miller is fortunate to work among a team of adults working to get elementary readers back on track: her school has a strong team of literacy interventionists who provide extra reading help throughout the day, as well as a first grade teacher focus group where tips and strategies are regularly exchanged. Miller and other early elementary educators maintain a fine balance between stretching their students while not pushing too hard with remediation efforts.

Although the pandemic has created many issues, it has also propelled educators and legislators to respond to long-standing deficits in students’ reading performance, as evidenced by major curriculum shifts, state-funded training for educators in the science of reading, and literacy nonprofits. Team Read, a free program that pairs trained teen reading coaches with second and third graders, is one example of a locally-minded nonprofit working to close reading gaps with a unique cross-age model. Local and regional efforts, coupled with the ingenuity of individual teachers like Miller, ultimately provide hope that young readers will bounce back. The case study at Doss Elementary illustrates the value of splitting a classroom into skills-based rotation groups and participating in teacher focus groups, as well as creating more time and space for reading beyond the classroom. Perhaps now more than ever, reading is a science as well as an issue of accessibility, requiring a creative and collaborative array of teachers, legislators, and nonprofits to support classrooms reading at multiple skill levels.

Take-Aways:

- Prolonged virtual literacy instruction has resulted in many elementary classrooms reading at different skill levels, creating instructional challenges for teachers.

- Heather Miller, a first grade teacher at Doss Elementary in Austin, TX, is one of many educators who have tailored their curriculum to support the varied needs of individual students in their classrooms.

- Innovative strategies employed by Miller and other educators, funding for teacher training in the science of reading, and support from literacy specialists and nonprofits are essential to the advancement of young readers returning to in-person instruction.

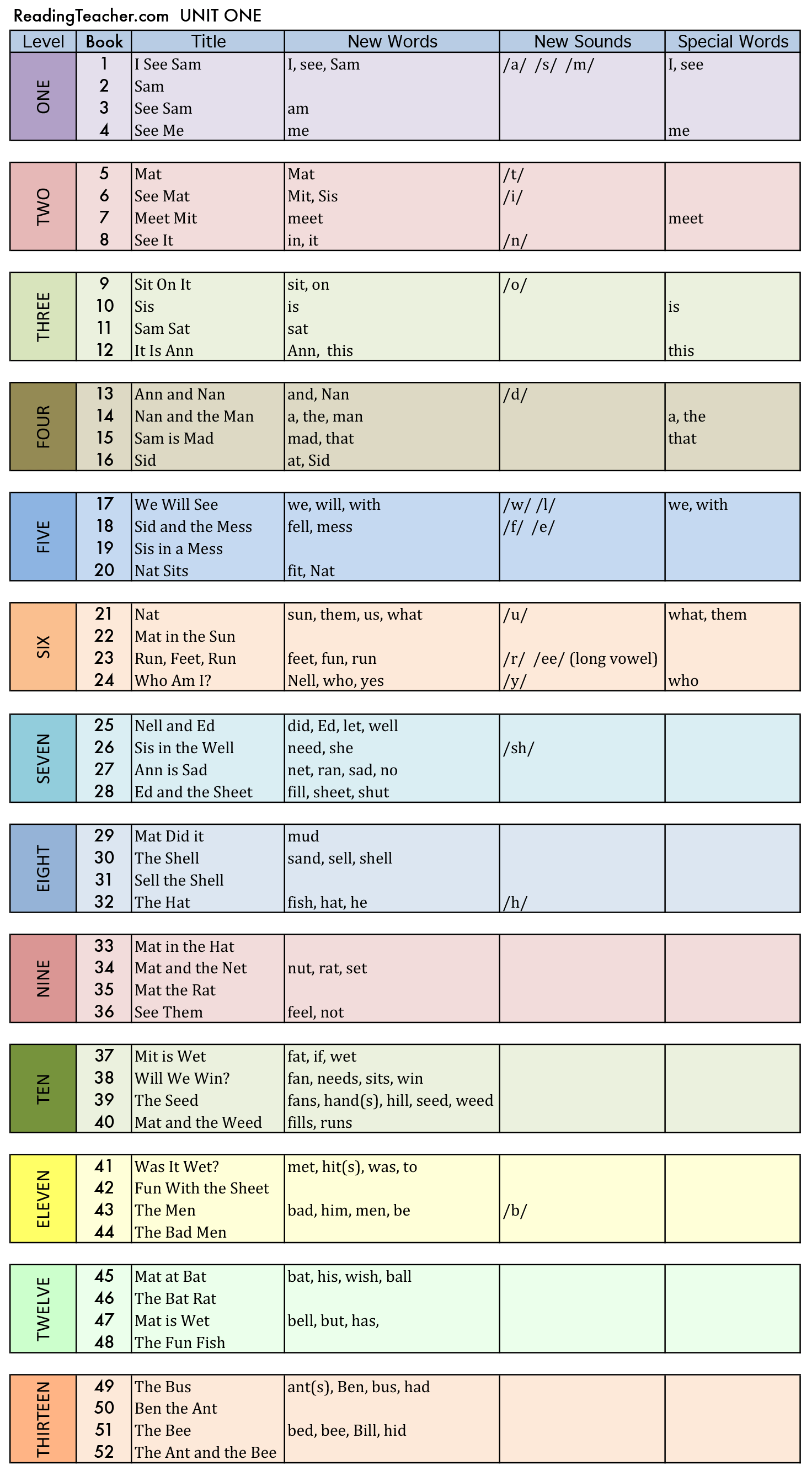

Start Teaching Reading for Free Now!

Access Level 1’s four interactive stories and the accompanying supplemental resources to teach elementary students how to read. No credit card is needed. Join the 42,635 teachers and students using our reading program.